SUSTAIN THE NETWORK

Once networks have been discovered and more networked ways of working activated, the third and final step is to sustain them. Sustaining networks turns out to be much less about control and much more about curation. Based on my experiences at the Center for Creative Leadership and more recently, Juniper Networks, I focus on helping leaders and organizations make the right investments in three areas – talent, culture, and structure.

Talent

Talent management involves an organization’s ability to continuously attract, develop, and retain people with the capabilities needed for current and future organizational success. Career development approaches in organizations traditionally focus on preparing people for vertical advancement to higher levels of responsibility. And all too often, technical skills are the sine–qua–non for advancement decisions. But to develop individuals’ capabilities to operate in boundary spanning networks, career pathways need to look less like a vertical ladder and more like a zigzag. And they must broaden the focus beyond technical skills to include relational skills, the ability to influence without authority, and to collaborate across organizational boundaries. I work with organizations to adapt their talent systems, while building leadership capabilities to work in more matrixed, networked ways.

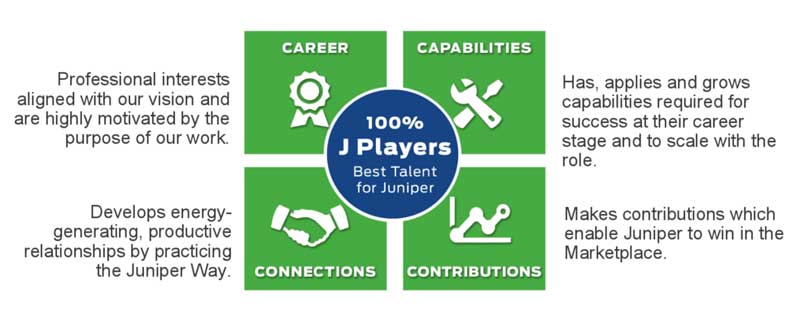

For example, as has been well documented by the CEB and other leading sources, Juniper was one of the first large global corporations to get rid of traditional performance management ratings. In its place are frequent “conversation days” for the purpose of open discussion around goals, areas for improvement, and career aspirations. Less well known is that in reimagining how talent is managed, we also included “the quality of connections” as one of the four expectations of performance, along with career, capabilities, and contributions. As Greg Pryor (my long-time colleague who played an instrumental role in this work) explains, this seemingly small change has had a big impact on how to build, reward, and sustain network effectiveness in the talent equation. Today, more than 97% of Juniper employees are considered “Best Talent” for Juniper, and talent management is squarely focused on getting the right capabilities in the right places to achieve business results.

An organization’s talent efforts should address the following types of questions:

- What individual capabilities must be developed if we are to enable networks, and more networked ways of working, to flourish?

- What experiences and support should be provided to improve boundary spanning capabilities among our people?

- How do we recognize and reward individuals and teams for engaging in collaborative work?

Culture

Organizational culture can be defined in many ways, but a solid starting place is offered by Ed Schein, one of my mentors and founding father of culture research. In Schein’s words, culture is “a pattern of shared basic assumptions that a group learns as it solves its problems of external adaptation and internal integration.” Interestingly, as organizations shift from hierarchical to networked forms of work, culture and the values associated with culture become critically more important. In its 2012 CEO Study Leading Through Connections, IBM found that as CEO’s focus on ratcheting down formal control systems, they recognize the need to ratchet up a strong culture that provides a clear sense of purpose to guide decisions and actions. I guide organizations to understand the culture they have and develop the culture they need to enable boundary spanning behavior and networks to thrive.

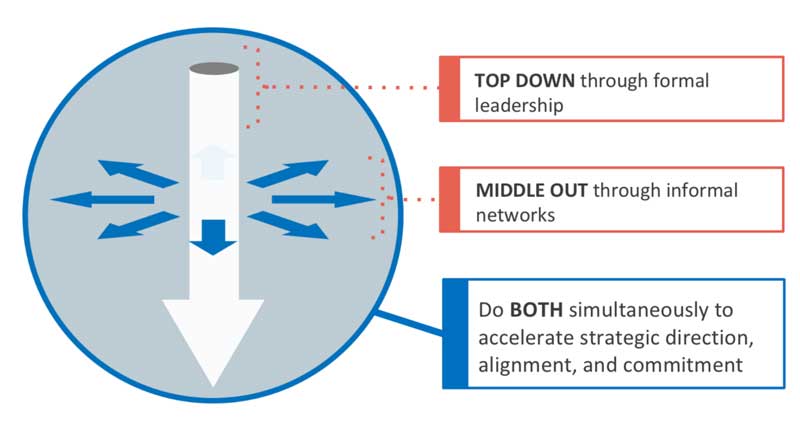

For example, when Rami Rahim rose to become CEO of Juniper in 2014 (beginning as employee #32), a first order of business was to reinvigorate the company’s unique culture, a set of values and behaviors known as the Juniper Way. The values had taken a backseat in recent years and company performance began to slide. In Rami’s mind, these two things were intimately related. Given the many ways in which networks and boundary spanning had already taken hold, I worked with Rami and a subset of “connectors” – informal opinion leaders – to strengthen organizational culture both top-down and middle-out. While Rami used his formal CEO platform to personalize why the Juniper Way is essential to delivering results, connectors informally engaged in peer-to-peer dialogue about why Juniper’s culture is meaningful to them. The result? Nearly every company performance measure is up. The Juniper Way culture is back. Cross-boundary collaboration and alignment is stronger than ever. And Juniper’s share price is riding a four-year high.

An organization’s culture development should explore questions such as:

- What type of culture do we have, and what type of culture do we need, to foster boundary spanning networks?

- What are the enablers and what are the blockers to making the necessary shifts in culture a reality?

- How can we actively support culture change to enable new thinking, beliefs, and behaviors to take root and spread?

Structure

Organizational structure defines how activities such as task allocation, coordination, and supervision are directed towards the achievement of organizational goals. When it comes to structure, the question is not “what type of structure is best” but rather “what structure does my team, unit, or organization need given its strategy and context?” On one end, there is command-and-control hierarchical models such as traditionally associated with the military. On the other, there are emerging new models like holacracy, that replace hierarchy with self-managing teams, no managers, and a flat organization, such as the bold experiment at Zappos. But as a practical matter, the far majority of organizations are somewhere between these two ends of the continuum – not dogmatic about hierarchy nor ready to go all-in on holacracy. Within this context, I help organizations to adapt or optimize their formal structure, while also activating informal networks to spur problem-solving, innovation, and change.

For example, at Juniper Networks, we once had 11 business units in engineering whereas there is just one today. Across the company, leaders ripped out business units, broke down P&L’s, and integrated the business like never before. It’s now the simplest operating model in Juniper’s history. Accountability is clear. Decision-making is fast. And market agility and speed is dramatically improved. Additionally, over the last 18 months I spent with Juniper, we put a significant effort into what we called Juniper Connectors, about 5% of the company who we identified as naturally playing connecting roles across the company. In 2014, we send out an employee survey asking about three key questions: Do you know our strategy? Do you understand your role in executing that strategy? Do you feel inspired and accountable to help the company achieve it? We didn’t hit 50 percent agreement on any of those statements. So, we put both the formal and informal structure to work. First, our executives hit the road to talk about the specifics of our strategy with teams in every corner of the company. And, we created space and tools for the Connectors to engage in candid peer-to-peer conversation. Four months after the initial survey, a second survey found all three indicators were above 80 percent.

Personally, I’m betting that networks will fill the space between the organizational structures of hierarchy and holacracy for years to come. Rather than blow up the whole system, a strategic approach is to operate in both ways simultaneously – formal and informal, top-down and middle-out.

Decisions and choicepoints around organizational structure should focus on the following types of questions:

- What type of structure do we have, and what type do we need, given our business strategy and context?

- In what ways does our structure support consistency, rigor, and efficiency? And in what ways does it support adaptability, innovation, and experimentation?

- How can we balance and integrate our formal and informal structures to achieve the best that both has to offer?

Sustaining the network is about building new capabilities – through integrating talent, culture, and structure – that change how work, works.